The Problem is Foreign Women

Sermon by Rev. Steven McClelland on Nehemiah 13: 25 – 30, John 4: 5 – 29. Focus on why blaming foreign immigrants is nothing new but something God does not condone. Check out Kelly Crandell, Lidya Diaz and the choir after the sermon as they sing – Ready!

This story is an excellent case study in crossing social, political and religious boundaries, and in it Jesus models for us a way to break the cycle of shame and violence between peoples, of differing perspectives, cultures and traditions.

Violence in most cases proceeds from a sense of shame, with the perpetuators of violence lashing out at whatever or whoever they’ve projected their shame onto. This in turn leads to a spiral of violence, as those ashamed of being bullied become bullies and the abused become abusers, and the cycle of shame and violence continues, or even escalates.

That cycle of shame and violence doesn’t have to continue, though; Jesus showed us a way out of it. And this Sunday’s gospel is an excellent case in point.

Jesus is traveling through Samaria, a land populated by Samaritans, whom Judeans despised. It wasn’t always that way. But in 586 BCE, the King of Babylon conquered Israel, destroyed the Temple that Solomon had built and enslaved the political and religious leadership of Jerusalem.

The phrase “time heals all wounds” did not apply to Israel. Like most people the Judean’s were looking for someone to blame long after the exile had ended. Trying to make sense of why God would have allowed this to happen the Judean’s found it convenient to blame their Samaritan brothers and sisters, the northern tribes of Israel, for the exile. After all there is no hate like brotherly hate.

The charge leveled against them was their foreign wives had lead them astray from God’s ways, never mind that the prophets had told Israel and Judea that it was for failing to grant justice to the orphans, widows and foreigners in their midst. So Judean leaders like Ezra and Nehemiah demanded that all such men immediately divorce their wives, passing along the experiences of humiliation, abandonment, and exile.

Not to surprisingly most of the Samaritan men refused which led to this humiliating treatment by the leaders in Judea of their brothers and sisters to the north. In Nehemiah’s own words:

I contended with them and cursed them and beat some of them and pulled out their hair; and I made them take an oath in the name of God … Thus I cleansed them from everything foreign… – Nehemiah 13: 25 – 30

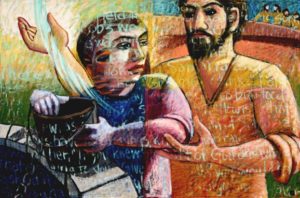

And so began the hatred between Judeans and Samaritans that was centuries old now by the time Jesus came to Jacob’s well, and was approached by a Samaritan woman.

It was noon, in the heat of the day, a time when most women would be inside. Not a time you’d want to be lugging a heavy jar on your head. The other women went to the well early in the morning when the work wouldn’t be quite so hard, and the drudgery of hauling water would be eased by the fellowship shared with other women who’d gathered around the well.

But this woman was one of the people the other women loved to gossip about, and the fact that she showed up at noon was a sure sign that she wasn’t welcome at their morning social hour.

And yet as oppressive as the noonday sun was, it didn’t burn like the stares of the others in the village. So she goes to the well when she sure she’ll be alone. But she isn’t alone. Jesus is there, and he speaks to her, which is something men only did if they were propositioning a woman.

So having been used and discarded by so many men from the village she replies that she has none. Jesus agrees with her but not in the way she is used to being talked to. Jesus says, “You are right, for you have had five husbands, more than Elizabeth Taylor,” which if we were to put into our context would be like saying:

“You are right, of all the men that you’ve been with – none of them has truly loved you.”

This poor woman has had her dignity taken from her by so many men that the intimacy of this conversation with Jesus throws her off balance.

So she changes the subject back to religion, trying to draw him back into an argument about Jews and Samaritans. You can hardly blame her. If he knows about all her husbands, there is no telling what else he knows about her, and she decides she’d rather not find out.

But it doesn’t work. When she steps back, he steps toward her. When she steps out of the light, he steps into it. He will not let her retreat. If she’s determined to show him less of herself, then he will show her more of himself. “I know that Messiah is coming,” she says, and he says, “I am he.”

This is amazing! It’s the first time he has said that to another human being, and a Samaritan woman to boot. It’s a moment of full disclosure, in which this ultimate outsider – this Samaritan woman and the Son of God – stand face to face with no pretense about who they are. Both stand fully lit at high noon for one bright moment in time, while all the rules, taboos and history that separate them are exposed and evaporate in the high light of day.

When Jesus confirms her identity as a woman who has been married five times, he is confirming a truth about this woman but by confirming this truth he sets this woman free. By not judging this woman by simply acknowledging the truth of what she had lived through he shows this woman support.

The Messiah is the one in whose presence you know who you really are the good and bad of it, the all of it, the hope in it. The Messiah is the one who shows you who you are by showing you who he is. Someone willing to cross all boundaries, breaks all rules, drops all disguises–speaking to you like someone you have known all your life. And when this happens she goes back into her own village. The village where she has been shunned and says joyfully: “Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done.”

What transformed this woman could transform our world. The woman at the well was despised by her village, and this northern village in turn was despised by the southern tribe of Judea, the brothers of the Samaritans, whose ancestors had been humiliated by the Assyrians and Babylonians.

From generation to generation – humiliation, resentment, and violence were passed down by people keeping score so that they could even it. Jesus is trying to show us how to break this cycle of shame and violence. The only question is – Are we willing to learn? Amen